Bringing Georgia to the World: Georgia Power Helps Make Olympic Dreams a Reality

Games' Impact Continues Today

A few minutes after sunset on September 26, 2014, André Benjamin and Antwan Patton – better known by their stage names, André 3000 and Big Boi, stepped out onto a temporary stage constructed in the middle of Downtown Atlanta and looked out at the first of three sold-out crowds of 20,000+. Their group, OutKast, was finishing a reunion tour in their hometown. The venue they chose for this performance, Centennial Olympic Park, did not exist when they began their career, but like OutKast themselves had become synonymous with the very idea of Atlanta. Today, it remains one of the many reminders of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games lasting impact on Atlanta and the state of Georgia, and the unlikely road that brought Georgia to the world.

By 6:30 in the morning of September 18, 1990, a crowd of several hundred had already gathered at Underground Atlanta – where the mood could only be described as “celebratory.” There was music and dancing as early risers from around the state trickled in charged anticipation of the long-awaited announcement.

Nearly 7,000 miles away, the mood in the Takanawa Prince Hotel was decidedly more reserved. The City of Atlanta was first on the list to make its final presentation to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for its longshot bid to host the 1996 Olympic Games. Once the presentation was over, the only option for everyone was to sit and await the final announcement. In attendance that Tuesday in Tokyo were members of the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) including Billy Payne, Mayor Maynard Jackson, and former mayor and U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young, along with representatives from Atlanta’s corporate community including contingents from the Coca Cola Company, Bank of America, and one of the committee’s earliest and most ardent supporters – Georgia Power.

Atlanta’s push to host the Centennial Olympic Games began in earnest in 1987, when Billy Payne, a lawyer from Athens with a penchant for fundraising, outlined his idea to try and bring the Games to Georgia to a friend with deep ties to Atlanta’s business community. The story, perhaps apocryphal, says that the next morning the friend appeared in Billy’s office window with a check for the amount Billy had thought he needed to get started.

Payne turned immediately to Atlanta’s business community, and Georgia Power was among the first to agree to a partnership.

Georgia Power’s deep connection to Atlanta and the state beyond would prove vital to the cause. Early on, Georgia Power leadership pledged to “bring Georgia to the world,” designating a team of volunteers to host IOC officials on their visits and introducing them to a distinctly Georgian brand of hospitality and citizenship.

From their first visit through the announcement of the Games’ location, every delegate from the International Olympic Committee who visited the state of Georgia was driven exclusively by a Georgia Power employee. These hosts were assigned to specific members of the committee and over the years built strong relationships with them, so that not only were they seeing what Atlanta could offer to the Olympics, but how we would make it our mission not only to hold a successful competition, but to show in earnest the spirit of unity and brotherhood that make the Olympic Games such a unique event in a divided world.

The moment of truth came that September morning, with thousands of Georgians now gathered at Underground Atlanta and nearly 400 Atlantans scattered around the ballroom of the Takanawa Prince Hotel. Four years of planning, organizing, and showcasing came to a head when IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch took to the podium to announce that the Centennial Olympic Games of 1996 would be held in the City of Atlanta.

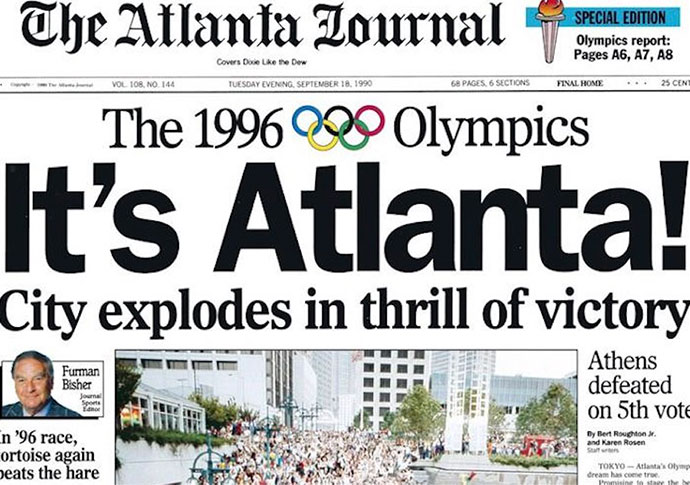

The front page of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution after Atlanta won its bid for the 1996 Olympics.

The front page of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution after Atlanta won its bid for the 1996 Olympics.

While the ballroom at the Takanawa Prince exploded into cheers as the announcement was made, with Ambassador Young and Billy Payne embracing through tears in the front row, the response was nothing compared to the scene in downtown Atlanta, where a crowd of now thousands erupted into thunderous applause along with singing and dancing as fireworks exploded above their heads in the mid-morning sky.

After four years of preparation, the popular “We want the Games!” chant had rendered itself obsolete. Atlanta had the Games, and now the real work would begin.

If Georgia Power had been a major factor in securing the Olympics, the company’s role there paled in comparison to their preparation and execution. But first, a party was in order. Georgia Power arranged a statewide celebration, sending the Olympic flag on its arrival from Barcelona on a train tour around the state before it visited the rest of the country.

Before preparation could begin on the ground, the company produced a two-page intent document with the two main objectives for the Olympic Games: to keep the lights on, and to showcase the state of Georgia. Everything Georgia Power did from that point forward kept those ideas at the forefront, and the company did everything it could to ensure that those objectives were fulfilled. Every Olympic venue was assigned a Georgia Power “venue captain” who would coordinate both with IOC officials as well as contractors and venue staff to make certain that the events held in those locations would go smoothly. Georgia Power built or boosted infrastructure at key points in Atlanta and beyond to create redundancies that ensured that venues, housing, transportation, or broadcasting centers would never be without power – even going so far as to construct temporary on-venue housing for line crews so that in the event of an outage there would be a crew immediately available.

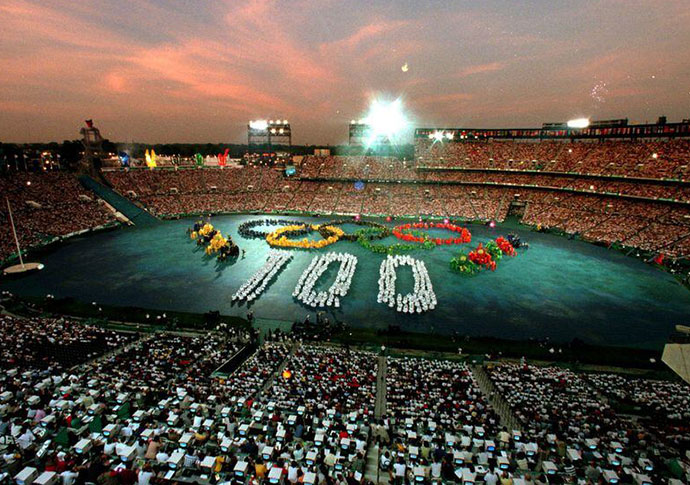

Thousands gather at the Opening Ceremonies of the Centennial Olympic Games. Every volunteer on the field was a Georgia Power employee.

Thousands gather at the Opening Ceremonies of the Centennial Olympic Games. Every volunteer on the field was a Georgia Power employee.

Georgia Power’s most important contribution to the games, arguably, was people. Thousands of Georgia Power employees volunteered for the Games on top of their job duties, including 2,000 who were on the field for the opening ceremonies, and those who volunteered to staff the 14,000 square foot hospitality tent on the ground at Georgia Power Headquarters in Atlanta which hosted a Georgia-style whole hog barbeque every night for more than two weeks for Olympic staff and volunteers. The company continued to host officials and dignitaries, drawing on the relationships built in the years both before and after the announcement was made. Many of those relationships continue to this day.

When it was all said and done, the Centennial Olympic Games generated more than $5 billion in economic impact to the city of Atlanta in the summer of 1996, bringing more than 1 million visitors and creating over 75,000 jobs. It was a catalyst of growth for the state which continues to grow at one of the fastest rates in the country. In the years since Juan Antonio Samaranch made the announcement that Atlanta would host the Centennial Games, the population of Atlanta has more than doubled, and the population of the state of Georgia has increased by nearly 70%, both numbers that far outpace the average rates of growth for American states and cities. Georgia has established itself as one of the most important states in the country for technology, innovation, logistics, and entertainment while being named the best state in the nation in which to do business for more than a decade consecutively.

The physical fingerprints of the Games can still be seen all across Georgia. From Folk Art Park near the downtown Atlanta headquarters of Georgia Power, to the various stadiums and venues constructed for the Games, and of course to Centennial Olympic Park, which now serves as a centerpiece to a revitalized and reinvigorated downtown tourist district. A trip down Hank Aaron Dr from Summerhill will still take you by the Olympic Cauldron, lit by Muhammad Ali, that continues to stand sentry over the former Olympic Stadium, itself now in its third act as the football stadium for Georgia State University.

The Centennial Olympic Games changed the way the world saw Atlanta as well as the state of Georgia. As Georgia continues to grow, both in stature and population, we celebrate the unlikely coalition that fought to make it happen.